Time for some ‘truth telling’!

What is Australia Day?

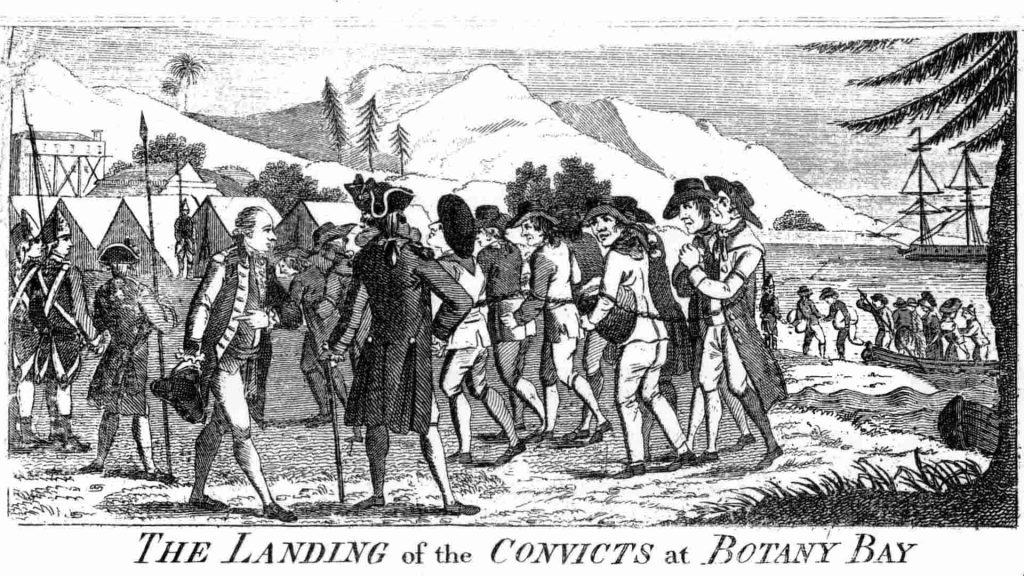

Australia Day is a national public holiday observed on 26 January – the day of the landing of the First Fleet in 1788 in Port Jackson (Sydney Cove) – after a false start at Botany Bay – which became Australia’s first colony and evolved into the City of Sydney. It is effectively the Foundation Day of New South Wales.

The First Fleet was made up of 11 ships: 2 Royal Navy vessels as escort; 3 store ships; and 6 convict transports led by Captain Arthur Phillip (later the first Governor of the colony). There were over 1500 people who started the voyage. According to diary records it’s believed 1483 made it to Sydney Cove. According to Captain Phillip’s official report there were 1030 plus 7 horses, 29 sheep, 74 pigs, 6 rabbits and 7 cattle.

It is believed over 700 convicts were transported on the First Fleet – including both men and women. Most were British but there were also American, African, French and Indian. (Over the next 80 years British courts sentenced more than 160,000 people to transportation.)

The four companies of marines were volunteers and their families also travelled with them. It was generally believed that no one would make the journey back other than the naval vessels that returned and supply ships that went on to other ports.

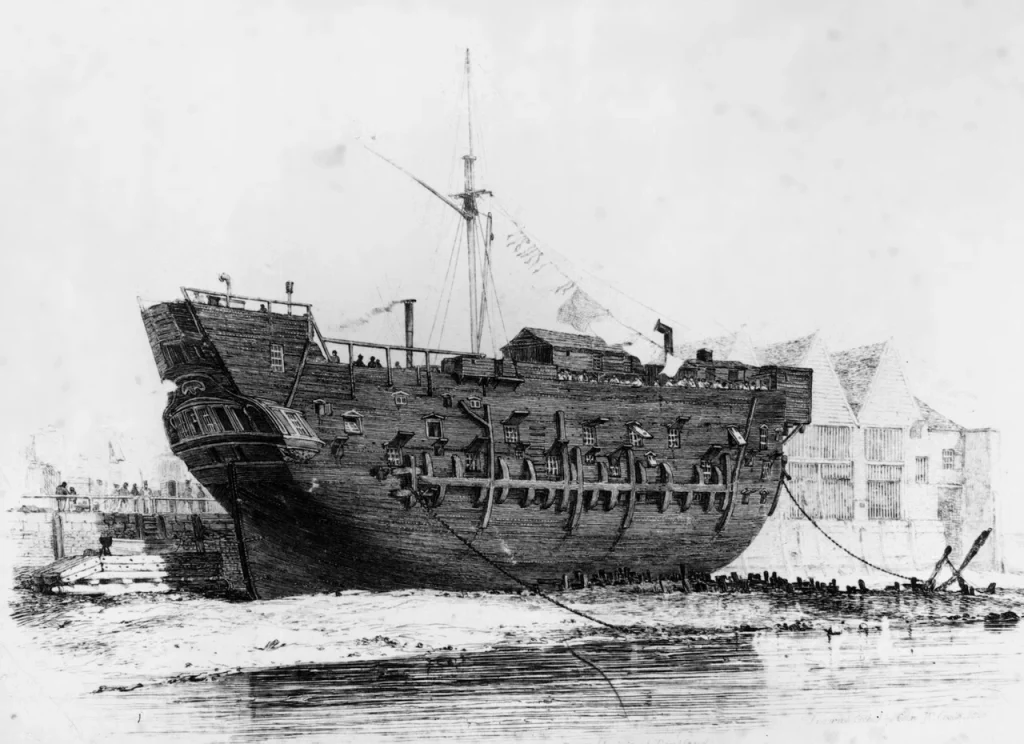

The convicts were transported because at the time English prisons were seriously over-crowded – to the point they were utilising “hulks” (prison ships) to deal with it. Transportation as far away as possible was the perfect solution. Convicts were transported for a range of crimes including theft (some just a loaf of bread), perjury, fraud, assault – for terms of 7 or 14 years – or life.

The party were expected to rely on their own provisions until local materials could be utilised, grow their own food and raise livestock. They were sent with seeds more suited to a northern climate – and about two years of provisions. After that, they were on their own.

The British government considered the First Fleet “an experiment”. The first colony was most decidedly a penal colony – not a settlement of free men and women. Every governor of the colony before Lachlan Macquarie (Governor of NSW from 1810 to 1821), apart from Governor Phillip, viewed the settlement as nothing more than a naval base with convicts as the labour force.

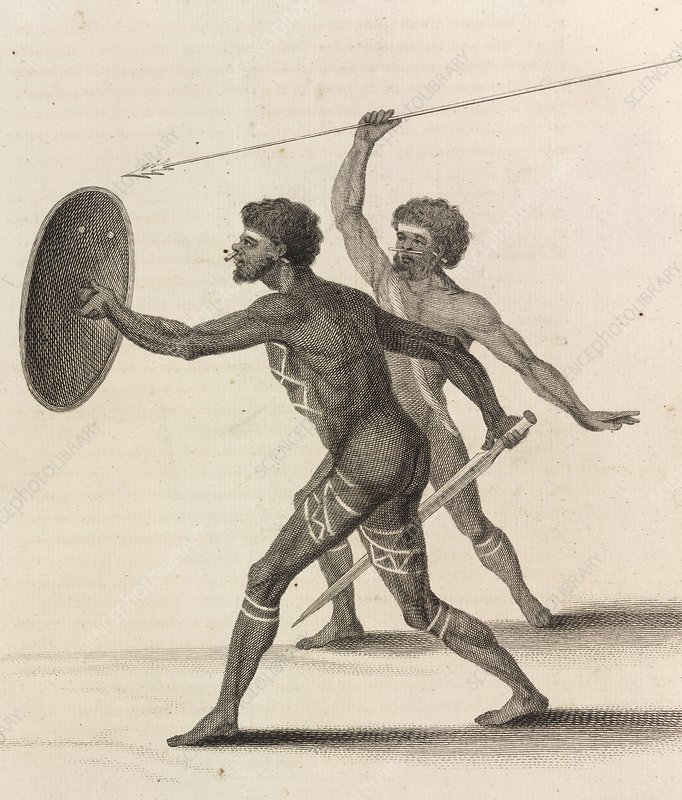

First contact was made with the indigenous population – the Cadigal people – at Botany Bay, and later in Sydney Cove when they encountered the Eora including the Bidjigal clan. There was ‘curiosity’ but no violence. Aboriginal men were sent to investigate the new comers, as was the tradition – and it is believed Manly received its name from Captain Phillip out of respect for the aboriginal men he first encountered there. The native men were curious and suspicious but not violent or aggressive – though they greeted the strangers with spears. They were trying to ascertain why they were there – who they were, were they women (as it wasn’t obvious; they were clean shaven – so Phillip ordered one of his men to drop his trousers to clear that up), and whether they would be competition for resources.

Invasion?

As an ‘invasion force’ this was probably the worst in military history. Despite the fact ‘invasion’ took place 18 years after the eastern coastline of the continent was mapped by Captain James Cook in 1770, it was comprised of a bunch of bedraggled prisoners in manacles, barely looked after by disinterested – often drunk – marines (whose nickname became The Rum Corps as later, rum became the currency of the colony).

Captain Phillip’s orders and the policy of the British Government of the day included that: “The aboriginal peoples’ lives and livelihoods were to be protected and friendly relations with them encouraged”. Specifically:

“Phillip’s official orders with regard to Aboriginal people were to ‘conciliate their affections’, to ‘live in amity and kindness with them’, and to punish anyone who should ‘wantonly destroy them, or give them any unnecessary interruption in the exercise of their several occupations’.”

Prof. Grace Karskens, 2017 – State Library of NSW Collection

The orders from (later) Governor Phillip were that aboriginal people should be well treated and reprisals discouraged. He wrote that he hoped to “give them a high opinion of their new guests” through kindness and gifts.

These orders were not unique but standard orders for the time – and not the behaviour typical of an invading force.

Early meetings with indigenous people in Botany Bay and Port Jackson were often friendly, including gift giving and curiosity on both sides – which is markedly different from other violent encounters between Europeans and indigenous people elsewhere.

As a defending force it took the Bidjigal another two years to launch a series of unsuccessful attacks against the colonists once they realised they weren’t leaving – as Cook had.

Not yet painting a picture of invaders and defenders.

Traditional aboriginal warfare took place over three main areas: competition for resources, reprisal attacks, and raids for women. The majority of the conflicts between colonists and aboriginal people took the first two forms, and occurred primarily after colonists pushed west of Sydney, opening up pastoral land, and exploration took them north and south – expansion that occurred during the 1790s and into the 19th Century. However it is recorded that five unarmed convicts were killed only a few months after the landing when they were seen catching fish and clearing land. (This set the tone for the later conflicts which were, as stated, primarily around competition for resources – not in defence of country.)

Despite this, Governor Phillip continued to forbid reprisals even after he was speared in 1790. It is believed the reason was he understood it was ‘payback’ (part of indigenous law) for the kidnapping of Bennelong – an act which was a misguided attempt to expose the local indigenous people to British culture in the hope it would lead to peaceful co-habitation.

To be fair, traditional aboriginal warfare was not like what we typically understand war or ‘defence’ to be. There was no coming together to defend the shore as an ‘army’. And nor could there be. There was no one unified ‘aboriginal people’. At the time of the First Fleet landings, it is estimated there were around 700,000 aboriginal people here, divided into different tribes consisting of different clans and all speaking different languages. These tribal groups had their own ‘countries’ and existed within that space utilising the resources it afforded. This meant that over the course of time, explorers and colonists came into contact with different tribal groups who reacted differently to the new comers. Sheer weight of numbers would have meant the failure of colonisation had the indigenous population been a unified, ‘sovereign’ group.

Conflict

Pastoral expansion meant competition for resources and this is when relations became hostile. However not in a systematic or organised way but rather between groups of colonists and individual indigenous groups. Even Governor Phillip changed his view when he reinforced the detachment of soldiers at Parramatta to protect the farms run by ex-convicts there. We can’t be surprised he acted like a military man with orders to ensure the new colony did what it was expected to do.

The first conflict occurred in 1795 – seven years after the ‘invasion’ – when farms which were established along the Hawkesbury River as a form of food security were raided by the Darug people.

Most of the conflicts were much later – during the mid 19th Century – 80 years and a full generation, maybe two, later, and therefore had nothing at all to do with the First Fleet landings – or ‘invasion’ – and are therefore far removed from the 26 January date. So it’s incorrect to link the ‘frontier’ conflicts with the First Fleet. Pastoral expansion could be the one aspect of colonisation that could even remotely be considered ‘invasion’, and that led to aboriginal raids on farms, constant attacks on unarmed settlers, Rum Corps reprisals and paybacks on both sides.

But not all indigenous people were resistant – a number served in mounted police units and later many as stockmen on what became large cattle stations. There are also many accounts of positive encounters with indigenous people especially by explorers like Charles Sturt and the lone survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition.

Whilst it is important to acknowledge this start of ‘nation building’ and how it impacted indigenous people – which we have, and do, regularly, and now almost to the exclusion of any kind of white history telling (just because you don’t tell it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist) – it is also important to see both sides – and not through the prism of 21st Century morality. While we hear the land was ‘stolen’ from the indigenous people, we don’t hear about reprisal attacks, the spearing of cattle not for food but because they were drinking the water, the murdering of unarmed settlers (many of whom were dispossessed of their home in the first place and didn’t want to be here) – and more importantly we don’t hear anyone asking for an apology for that.

Why Celebrate?

Whilst it’s important to acknowledge the conflicts that took place from the time of pastoral expansion, and to acknowledge our history as a shared one, they have nothing to do with what Australia Day is about. The landing of the First Fleet was not met with any form of resistance in the traditional sense of repelling an invading force and not even in the traditional methods of indigenous conflict (which there indeed was at the time, rather than the peaceful utopia we’ve been led to believe was the order of the day prior to European arrival).

Australia Day is about commemorating the landing of a group of people who were forcibly removed from their country for committing, in many cases, petty crimes, and expected to eke out a living in a hostile land with a climate they weren’t ready for. They struggled for survival with no hope and no future.

Despite this, they managed to not only survive but through tenacity, will, courage and determination, establish a first world country that can match any other on the planet. They took their situation, made inroads into the west, built roads, towns and cities which still stand today, literally from what they found, often while shackled and being beaten, and set up primary industries still making money for the people of Australia today – including indigenous people. That formed the basis of who we are as white Australians but also who we are as simply, Australians.

We have a shared history that should be honoured and respected but also we should celebrate who we are as a nation. We have a history that includes struggle, hardship, and beating the odds. Literally being left for dead and surviving anyway. THAT is what Australia Day is about. THAT is worth celebrating!

Australia Without Colonisation by the British

What would Australia have looked like had colonisation not occurred? Would it look like the Australia we know now?

Let’s imagine there is a forcefield around Australia preventing the Spanish, Dutch, French, English or Asian explorers and cartographers from finding it. Would a primitive 40,000 (or 60,000 depending on who you listen to) year old culture have been able to develop Australia into what it is today without colonisation when only 250 years ago (not long in the scheme of things) they were still nomadic, naked, primitive people?

We already know what it would look like … North Sentinel Island in the Gulf of Bengal is a living example.

Industrialisation enabled countries around the world to evolve and develop and at the time of the First Fleet, industrialisation had not made it to Australia. Not even the wheel … Or pottery… a mere 235 years ago!

We know from the diaries of explorers to the remote parts of Australia, and settler accounts of encounters with indigenous people, even as late as the late 19th Century (1882 diary of Caroline Creaghe), that the indigenous population were wandering the country naked with rudimentary shelter (lean-tos and bark humpies) and primitive art and weaponry.

But the efforts of those early settlers – most of whom (except for the free settlers who began to arrive from 1793) didn’t want to be here but couldn’t leave once emancipated – have afforded us as an entire nation opportunities we may not have otherwise had – and that equality of opportunity is afforded to us all regardless of whether we are indigenous Australians, white Australians, or migrants, and regardless of who’s in the majority (indigenous Australians – 3%; migrant Australians – nearly 30%).

The Dutch were first to make landfall in Australia in 1606 – and it was named New Holland by Abel Tasman (with Tasmania being named Van Diemen’s Land) in 1644. But neither the Netherlands nor the Dutch East India Company claimed any territory – with most explorers claiming the lack of water and fertile soil made it unsuitable for colonisation. Had they not come to that conclusion, things could have gone in an entirely different direction.

Two words: South Africa….

Exploration, invasion and colonisation have happened the world over and for millennia – more often than not violently and with the forceful subjugation of the ‘conquered’ people. The Dutch, Spanish, French, English, Mongolians, Chinese, Romans, Celts, Picts, Arabs, Vikings, Egyptians, Pacific Islanders, just about every country in Africa … all come to mind. Where there are people there is expansion. In Australia, we’re expected to ignore our history as being “offensive” or “triggering” for a small percentage of our population, and worse, apologise for it.

This despite the fact that in the intervening 235 years the following days are set aside out of respect for our indigenous Australians:

13 February – National Apology Day

16 March – Close the Gap Day

21 March – Harmony Day

26 May – National Sorry Day

3 June – Mabo Day

27 May to 3 June – Reconciliation Week

1st week of July – NAIDOC Week

4 August – National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Children’s Day

9 August- International Day of World’s Indigenous People

7 September – Indigenous Literacy Day

This is also not to mention the countless “acknowledgements” we hear at just about every event, and that we are starting to (ridiculously) see on website footers and as pop ups – and the ‘Welcome to Country’ included in agendas, at sporting events, conferences, the opening of parliament etc – an indigenous ‘tradition’ that was developed in 1976 by Ernie Dingo and Richard Walley when Polynesian performers at the Perth Fringe Festival asked for one. It was “designed to mirror the visitors’ own traditions and incorporate elements of aboriginal culture”. Indigenous people do have a seeking and granting of ‘permission’ when one tribe wants to cross into the lands (or ‘country’) of another – but not as we see it now. The Aboriginal National Theatre Trust was instrumental in developing it during the 1980s.

It was in 1976, and it remains now, a performance.

Despite all of the above, the rest of Australia – including not just white but also migrant Australians – are told one single day out of 365, to celebrate where we have come as a nation, is ‘offensive’ and we should be ashamed and guilt-ridden if we do.

Which brings us to …

Changing the Date

This time of year always brings about discussion (okay arguments really) about changing the date from 26 January because it ‘represents invasion’ or a ‘dark time for indigenous people’ and is ‘offensive’ to them.

I’ve discussed above why the 26 January landing date and ‘invasion’ cannot coexist as a concept.

However, some Australians will ‘virtue signal’ and say they refuse to celebrate ‘out of respect’ for indigenous people who find it repugnant and a day of mourning. (Note the inference ‘all’ indigenous people – which could not be further from the truth.)

As I’ve said above, pastoral expansion is so far removed from the 26 January landing of the First Fleet as to make the argument moot.

The date was first recognised in 1808 particularly by emancipated convicts to “celebrate the love of the land they lived in” with “drinking and merriment” (sound familiar?). In 1838, on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the colony, the first public holiday was declared.

Up until 1888 the celebration was primarily confined to New South Wales – but in 1888 on the centenary of the First Fleet’s arrival, every colonial capital except Adelaide celebrated “Anniversary Day”. In 1910 South Australia came on board after the death of King Edward VII.

It’s probably worth noting that on the 26 January 1949, ‘Australian’ as a separate nationality came into existence when the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 was passed. That was the day we were first called Australians and allowed to travel with passports as Australians.

Under the Nationality Act 1920 (Cth), all Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders born after January 1, 1921, gained the status of British subjects. On 26 January 1949, therefore, they automatically became Australian citizens under the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948.

Before that date, all people living in Australia, including indigenous Australians, were called ‘British Subjects’ and forced to travel on British Passports and fight in British wars.

It wasn’t until an amendment in 1984 that we were no longer considered ‘British subjects’.

We all became Australians on the same day: January 26!

This is why 26 January is a key date, and appropriate for Australia Day and a national day of celebration.

Additionally, in 1962 the Menzies government gave indigenous Australians federal voting rights thus giving all Australians full political equality regardless of race, sex or creed. It wasn’t until 1965 African Americans were given the same right.

Side note: 26 January was also the day in 1808 when the fourth Governor of New South Wales, William Bligh, was deposed in the Rum Rebellion – the first and only time in Australian history military force has been used to overthrow a government. 26 January appears to be quite a key date…

Comment

If you want to boycott Australia Day because you feel indigenous Australians had a rough trot 235 years ago because a rag tag bunch of prisoners and drunken sailors landed on their shores, then that’s up to you. It’s not being done ‘out of respect’ though because boycotting a day that’s NOT just about white people but is for everyone who calls Australia home, does NOTHING to help with the actual issues facing indigenous Australians every day – like family and domestic violence, alcoholism, drugs, abuse, and black on black violence. Maybe use the public holiday to head out to the communities and get your hands dirty actually helping out.

And what about respect for the other people involved? Of those men and women and children sent here unwillingly who managed to survive despite the odds in a country literally out to kill them, displaying a toughness and resilience sadly lacking in us today – but which became the bedrock of our culture (yes, we have one) and enabled equality of opportunity for all. Men and women who even after emancipation and in the years between Governors Phillip and Macquarie, continued to be treated like prisoners and second class citizens – struggling for survival with no hope, no civic pride and no future.

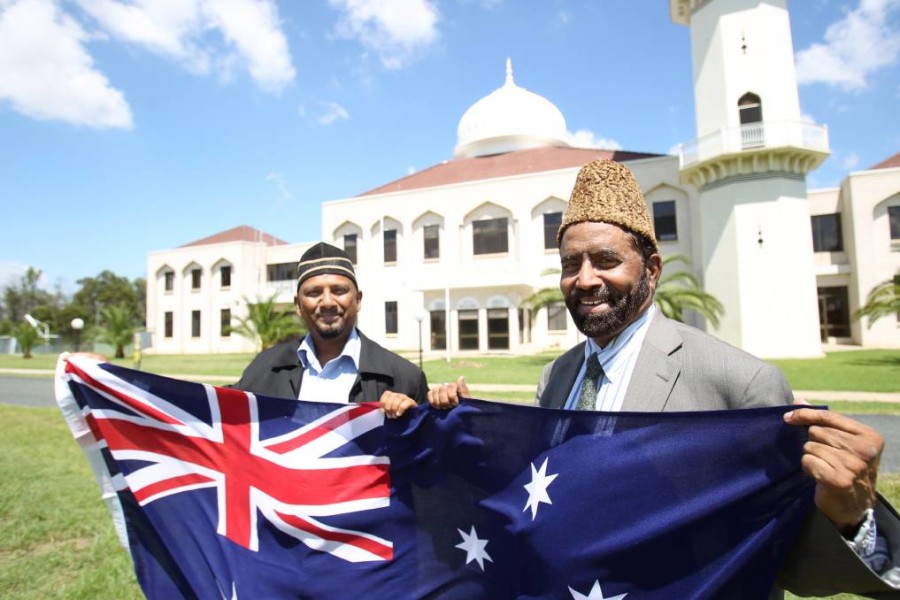

Or respect for the thousands of migrants who make up our number, who continue to come here – and who become Australian citizens on this day because they want a better life? Who didn’t have to steal a loaf of bread to get here but who are welcomed into what is a rich fabric of different cultures – to a country that allows them the freedom to practice their culture and religion without reprisals or restrictions?

Nearly every single country from around the world is represented in Australia’s population – nearly 30% of those living here are migrants. My own family are Jewish migrants on my mother’s side who came here in 1910; and Cornish/Celts on my father’s who came here as free settlers in around 1857 – for precisely the same reasons migrants do today: a better life which was afforded to them by Australia.

Absolutely it is important to teach both sides of our history, but unfortunately our kids are getting primarily, one. As Douglas Murray says in The Madness of Crowds, the pendulum has swung too far the other way and the train has crashed right on through the station. It’s time to stop the victimhood and guilt tripping, virtue signalling and apologist language, and unite to recognise there’s a reason why so many people WANT to live here!

The dates listed above show that inroads have been made into acknowledgement of 3% of our population, but it does make you wonder will it ever be enough? An apology was asked for and given – but that wasn’t enough. Acknowledgement of ‘wrong doing’ was asked for and given – but that wasn’t enough. Separate medical centres, organisations handling indigenous only issues, successful land titles claims, special educational bursaries, support and assistance given just for indigenous people (which to be honest I find particularly insulting as it infers all indigenous people need assistance, based purely on them being indigenous – and isn’t that the definition of ‘racism’?) – but that wasn’t enough.

No one blames Americans born after Hiroshima and Vietnam for what happened. No one blames Germans or Japanese born after WWII for what happened. But white Australia is still being blamed and expected to feel guilty for what happened nearly 250 years ago…..

When is it ever going to be enough?

We are all custodians of the land – all of us – black, white and migrant. All cultures – not just Australian indigenous – have connection to land and to spirit of place – including ‘white’ cultures. It is not unique.

We are all Australian. We have ONE day when we can come together and celebrate that. That day is 26 January.

Happy Australia Day!

© Earth Goddess Wisdom

References:

Plenty of resources went into crafting this post – here are a couple. I shall leave it up to the reader to research on their own.

https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/rum-rebellion

https://visitsydneyaustralia.com.au/lachlan-macquarie.html

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/first-fleet-sets-sail-australia

https://firstfleetfellowship.org.au/library/first-fleetlist-livestock-provisions-plants-seeds/

https://digital-classroom.nma.gov.au/images/map-indigenous-australia